The Framework

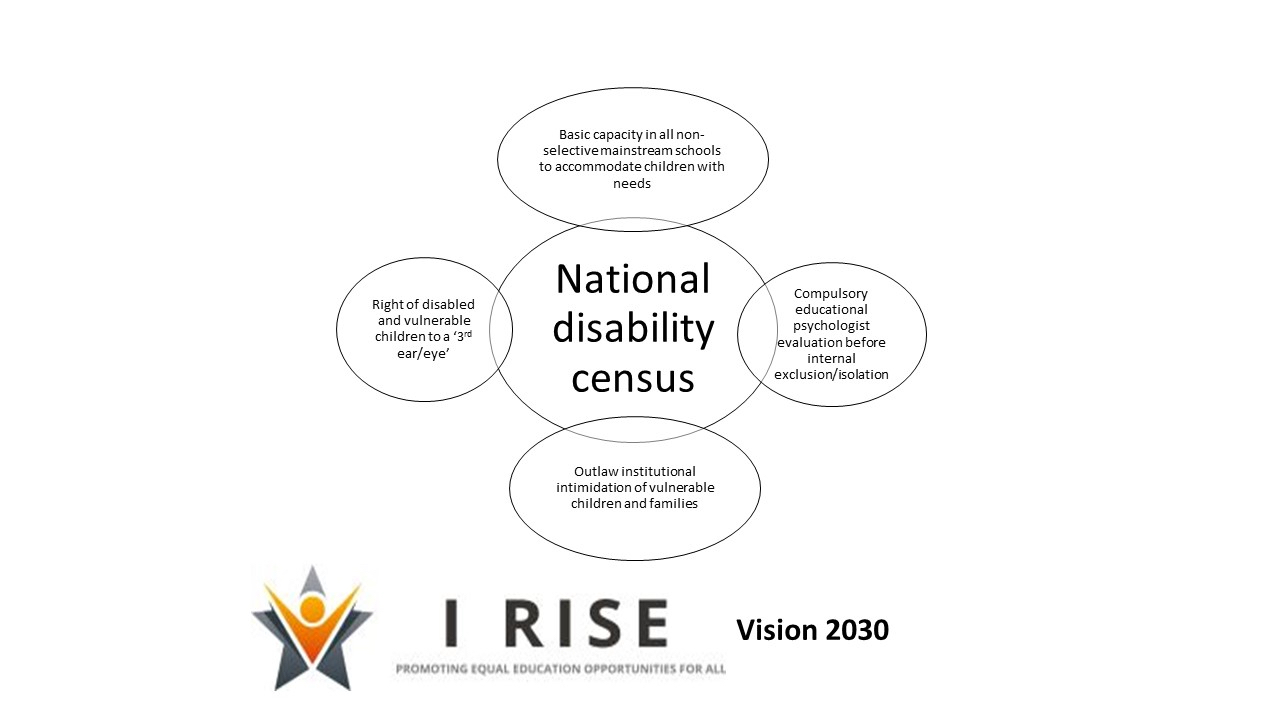

A National Disability Census

Present-day decision-making is largely informed and driven by data. Consequently, the availability or non-availability of data influences a whole range of issues. In the context of the matters related to children with special and additional needs, availability or non-availability of relevant data could readily promote a child’s case or undermine it.

Case study

There have regularly been situations in which children with needs in a particular school setting have required specific provision, equipment, specialist staff etc. Over a period of one year the same school denied all such children this provision.

They were able to do this by meeting with parents individually and denying them the same facilities, basing their argument on matters of ‘cost effectiveness’ (efficient use of resources). This was presented to appear that only the child whose parent was meeting with the school’s management required what was needed. In some cases, the school made this argument in the presence of officials from the local authority (LA).

If there had been a disability census the result of which were available on the school’s website, the school would not have been able to disadvantage the community it was meant to serve in the way that it was doing, and would perhaps continue to do. If children who require these facilities, provision, items etc regularly attend and/or request to attend a school, it is incumbent upon that school to have them in place rather than deny members of the community the service it should be rendering to them.

Such provision, equipment, specialist staff etc should be a standard feature in every mainstream school ten years after the Equality Act 2010 in the UK. Other sectors of the UK economy have acted proactively and devoted significant resources ensuring that the needs of individuals with special and additional needs are met. However, schools regularly go to court to defend their inability to meet these needs partly on the basis of cost effectiveness.

‘I rise’ notes that a concept such as provision of ‘teaching assistants’ (TAs) in school is not an original feature of schools, but something that has arisen over time because of an acknowledged need and has now become institutionalised. On that basis, as well as the principle of equality, ‘I rise’ believes that cost effectiveness should no longer be a reason for denying children with special and/or additional needs, whose parents desire a mainstream education for them, a place in mainstream schools. By now a provision such as specialist TAs should be a standard feature in mainstream schools.

Basic capacity in every non-selective mainstream school to enable children with needs to attend

In the UK, ten years after the Equality Act 2010 primary and secondary schools deny children admission on the basis of their disabilities and needs. The schools justify this on the basis of the conditions set out in case law when doing this: i) compatibility with the efficient education of other children[1]; ii) compatibility with efficient use of resources[2]. What is instructive here is that these conditions set out by the courts/tribunals, which may constitute grounds upon which children with needs may be denied mainstream education, are expected to manifest naturally in the course of schools caring for and supporting a child with special and/or additional needs.

However, what appears to happen in practice on many occasions is that some schools take action ‘to produce’ these conditions in order to achieve a situation that would enable them to argue against or deprive children with special or additional needs of their right to mainstream education.

Ten years after the Equality Act 2010 schools in the UK have made good progress. There have been significant achievements in terms of physical and structural provision such as the construction of ramps and provision of certain facilities. Other things which it should now be standard practice to provide in these schools in view of the length of time that has passed, such as speech and language support, sensory rooms and equipment, amongst many others, specialist teaching assistants (TAs) etc are still lacking and provide grounds for mainstream schools to discriminate against children with special or additional needs.

In the long history of school education in the UK provision of teaching assistants is a relatively new concept that came into being in the 1960s. It has not always been there. This brings to the fore the question: if the school system has found the need to institutionalise additional support in the form of TAs for children without needs or disabilities, why has it not institutionalised specialist TAs for children with special and additional needs in order not to disadvantage them in many different ways? What this means is that every year group should compulsorily have specialist TAs in addition to the regular TAs in a school. Moreover, the training and continuous professional development of regular teachers and TAs need to include special and additional education needs.

Special education needs co-ordinators (SENCos) are critical in the management of children with special and additional needs. They are supposed to be key players when it comes to supporting children with special and additional needs within the school system. However, that is not always the case in my experience and based on the feedback I have received from many parents. Many SENCos appear to operate as ‘gatekeepers’ determined to keep away children with special or additional needs, whom they appear to consider undesirable. In terms of supporting these children with special and additional needs, they do it more from a perspective of ‘ticking the boxes’ rather than truly caring for these children and meeting their needs. This has been my personal experience, which is consistent with feedback I receive from other parents over the past 7 years. This orientation needs to change.

[1] Hampshire County Council v R & SENDIST [2009] EWHC 626 (Admin) (2009) ELR 371; NA v London Borough of Barnet (SEN) [2010] UKUT 180 (AAC).

[2]Crane v Lancashire County Council [1997] ELR 377; Essex CC v the SEND Tribunal [2006] EWHC 1105 (Admin).

Case study

There are situations which regular TAs experience but for which they are not prepared. A child with autism who is very fit to attend mainstream education may need to be engaged in certain ways in order to encourage him/her to do certain things.

Lack of expertise could lead a non-specialist TA to handle such situations in ways that may not be appropriate through no fault of his or her own, which may trigger an adverse reaction or ‘meltdown’ on the part of the student. Possible outcomes of this situation are:

- The child will be labelled as violent, aggressive, disruptive, ‘to be attacking’, unsuitable for mainstream education etc.

- A situation may arise that would be described by the non-specialist TA as an ‘attack’. A specialist TA, would have the necessary understanding, professionalism and work ethic and would not describe such situation as an attack.

- In the context of this matter it appears that a completely vulnerable child with needs is expected to behave like an adult, rather than those adults who owe the child a duty of care. Consequently, the words and conclusions highlighted in numbers a. and b. above are used.

- After ten years of the Equality Act 2010 schools need to have basic capacity (personnel and tools) to enable every child (able, disabled, with additional needs) whose parents desire a mainstream education for them, to be able to have access to it.

Basic capacity in every non-selective mainstream school to enable children with needs to attend

Outlawing of internal exclusion/isolation for children with needs – without a formal educational psychologist report to guide the measure:

On a regular basis, in many cases without the knowledge and/or consent of parents, vulnerable children with special or additional needs are isolated within schools. This is detrimental to the children’s development. It is imperative that no child is internally excluded/isolated without an educational psychologist’s evaluation and advice in any school for more than a school day.

Case study

A child’s Education and Health Care Plan (EHCP) required the school to maintain a daily record of the child for her parents in a designated home/school book. The school failed to maintain the home/school book. At a meeting between the school, the parents and the LA, the school argued that the child had become very disruptive and they could no longer care for the child. The school did not provide any shred of evidence. Every day when the parents of the child picked her up from the school, they were told that everything went well; consequently, they refused to take the child to a specialist school, as suggested by the school’s management.

The following week the school alleged that the child had had a ‘meltdown’ and isolated her. A visiting SENCo attended the school soon after to determine whether the child would be admitted to the main secondary school of her parents’ choice. The visiting SENCo noted that the child was, and I quote her directly: “being educated 100% in isolation from the other children.” Before this time other parents and staff in the school complained to the parents about the child’s isolation. In addition, the parents had noticed the isolation from time to time and raised the matter with the LA. The LA got back to the parents on each occasion, presenting the school’s excuses. The parents eventually went to an SEN tribunal regarding the isolation but lost the case because they believe the school ‘manufactured’ evidence (through the head teacher, deputy head teacher/girl’s class teacher, SENCo and TAs) to demonstrate that the child was not in isolation. The parents continue to pursue the matter with a view to upturning the tribunal decision.

What is instructive in this case, however, is that if the school had provided the visiting SENCo with the evidence, with which it later provided the tribunal, the visiting SENCo would not have written that the child was being educated 100% in isolation from the other children. She based her comment on the information provided by the same deputy headteacher/class teacher, SENCo and TAs. Of course, this vulnerable child is echolaic and consequently she says ‘yes’ to virtually anything, which the school exploited at the tribunal. When the school that was manipulating her asked her whether she was happy in the presence of people who did not understand her circumstance she said ‘yes’. The school extensively and mercilessly manipulated this innocent and vulnerable child, to whom they had a duty of care, to her own disadvantage. Basically, the school groomed and conditioned this vulnerable child into accepting what was not in her best interest because her parents insisted that the law be obeyed regarding their daughter’s education.

As a result of the deception and the manipulation of a vulnerable child, the school management left her in 100% isolation for the remainder of her stay in the school without an educational psychologist’s evaluation of the impact on her. The adverse effect of such treatment on this child and other vulnerable children that have been isolated/excluded internally may never be known, while these children continue to be blamed and punished by the school establishments through no fault of their own.

- After ten years of the Equality Act 2010 schools need to have basic capacity (personnel and tools) to enable every child (able, disabled, with additional needs) whose parents desire a mainstream education for them, to be able to have access to it.

Right of a vulnerable child/person to a ‘third ear’ and/or ‘third eye’, where necessary, for wellbeing and safety

It must be noted that the vast majority of schools, head teachers, SENCo, teachers and TAs do the right thing. However, it cannot be said that no head teacher, SENCo, teacher or TA does the wrong thing. Many parents and families of children with disability, as well as the children themselves, have had varying experiences from head teachers, SENCo, class teachers, TAs and other members of staff. What is disturbing about this matter is that the victims are not only children, but the most vulnerable of the vulnerable in the society. Even if it is just one child, Martin Luther famously pointed out that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”.

The case study above on the need for educational psychologist evaluation raises the need for vulnerable children to a ‘third eye/ear’, meaning that such children should have a right to electronic devices that would protect them. In addition to the issue of safety, these devices would also provide invaluable data that could be used by relevant professionals to help them understand the needs and circumstances of these children who are vulnerable and may not be able to provide reliable account of their experiences. Such devices would bridge this obvious gap by providing an independent and objective account of things.

Case study

A head teacher made a child protection referral against a parent, claim that a vulnerable and echoliac boy had disclosed that he had been smacked with a belt by the father. The head teacher had previously refused the child the right to transfer from a special school to the school; however, the father dad insisted that the right of the child with disability to attend mainstream education be respected. The LA honoured their obligation to the child and his parents and allowed the transfer.

In the course of the social services investigation into the alleged disclosure it transpired the head teacher had lied extensively to social services in violation of the school’s safeguarding policy. This was an extremely serious situation in which the head teacher should have no motivation whatsoever to lie. In addition to lying, the head teacher also violated so many laws: he abducted the child when he was almost home, using the force of the authority of his position and that of the LA’s social services; he failed to inform the parents of the child about the referral despite social services directing him to do so; he kept the child incommunicado without informing the parents; he deprived the vulnerable child of his medication, therapy and a meal; he went on a ‘lying spree’. Interestingly, a whistle-blower informed the parents that the head teacher was present at the time of the alleged incident and actually questioned the vulnerable child. The child, being echolaic, merely responded to the propositions of the head teacher. The social worker who attended did not bother to look at the child’s records. She was taken in by the head teacher’s lies and she staged her own questionable activities. On the head teacher’s second attempt at dubious disclosure, the father requested that his son should carry a recording device as he discovered that his son was isolated from his classmates, to enable the investigators to obtain objective and verifiable evidence of events, which would allow social services to indict him if the allegations were genuine. That marked the end of the dubious disclosures. Neither the head teacher nor the social worker reported the father’s request.

A ‘third ear and/or eye’ being made legally permissible for such vulnerable children to use such devices at the request of parents would moderate the chances of such institutional abuse.

- After ten years of the Equality Act 2010 schools need to have basic capacity (personnel and tools) to enable every child (able, disabled, with additional needs) whose parents desire a mainstream education for them, to be able to have access to it.

Guard against institutional intimidation of vulnerable school children and their families

Families of children with special needs have been subjected to institutional intimidation by schools, whose actions vary from pushing the children out of mainstream education into a special school to being vindictive.

Case study

Some head teachers and their collaborators within the school system regularly fabricate allegations against vulnerable children and their families and send social services after them. Social services have been unleashed on a family based on a primary school’s allegation that their autistic vulnerable daughter in year 2 used the words ‘F… you’. The head teacher wrote in the referral that the child used ‘a sexualised word’.

She went on to note that the child was always with her parents. Perhaps she had forgotten that the child walked in the street, used public transport, played with the other children, waited with her parents in the school ground while waiting to go into the school every morning. And in all of these cases/environments people regularly use swear words.

Interestingly, this is the same family that is reported in the case study regarding the right to a ‘third eye and/or ear’. Within a timeframe of about seven years, during which their twin children with disability were in mainstream education, social services were prompted to investigate this family about 5 times. Instructively, nothing was found on this family. They believe that they are being institutionally harassed for insisting on their disabled children’s right to mainstream education.

- After ten years of the Equality Act 2010 schools need to have basic capacity (personnel and tools) to enable every child (able, disabled, with additional needs) whose parents desire a mainstream education for them, to be able to have access to it.

CHANGE A LIFE TODAY

Get in touch today and start making the difference.